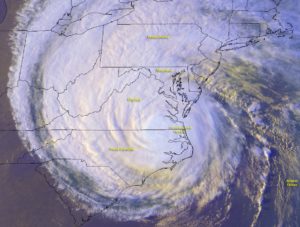

No natural disaster sparks the anxieties of Virginians quite like a hurricane. Many remember Isabel, which inundated the Hampton Roads area and pushed a nine-foot storm surge up the James to Richmond in 2003. Anyone unlucky enough to live in Nelson County in 1969 will never forget when Camille dropped 27 inches of rain and caused the deaths of 153 people.

This year, Harvey and Irma spared Virginia but devastated the Gulf coast with rain and wind, with Category-5 Maria lurking close behind.

Hurricanes are as American as apple pie, having occurred naturally for thousands of years. Over centuries, the southeastern coastal landscape adapted to reach a delicate balance with these powerful storms. Wetland trees and grasses grew resilient to floods and wind. Beaches and barrier islands shrank, expanded, and migrated to dissipate wave energy. Shorelines washed away by hurricanes were gradually repaired by sediment delivered downstream by rivers like the Rappahannock. Piece by piece, our coastline built a natural line of defense capable of absorbing some of earth’s most powerful storms.

As America grew and industrialized, we began to undermine our natural storm defenses. Erosion-resistant trees and grasses were cut and burned. Wetlands were drained, filled, and built over, leaving entire communities vulnerable to deadly flooding. Natural shorelines that once migrated to absorb storm energy were replaced with immobile bulkheads susceptible to wave undercut. Rivers like the Rappahannock were dammed, disrupting the movement of sediment and robbing the rivers’ ability to repair themselves after storms.

Chesapeake Bay Governor’s School students help install a living shoreline. Living shorelines help protect shorelines against storm damage.

Friends of the Rappahannock is actively protecting and restoring the natural infrastructure that forms the first line of defense against damaging storms. We are replanting native trees and re-establishing grasses in and around waterways. We are installing living shorelines that replace unsustainable bulkheads with natural, sustainable beaches that can resist storm surges.

We fought to remove the Embrey Dam and free our Rappahannock, and will continue to work to remove barriers that limit the natural processes that nourish our shorelines. And we’re educating the next generation to carry on that mission and protect our shoreline communities against the next Big One.

Adam Lynch

Restoration Coordinator