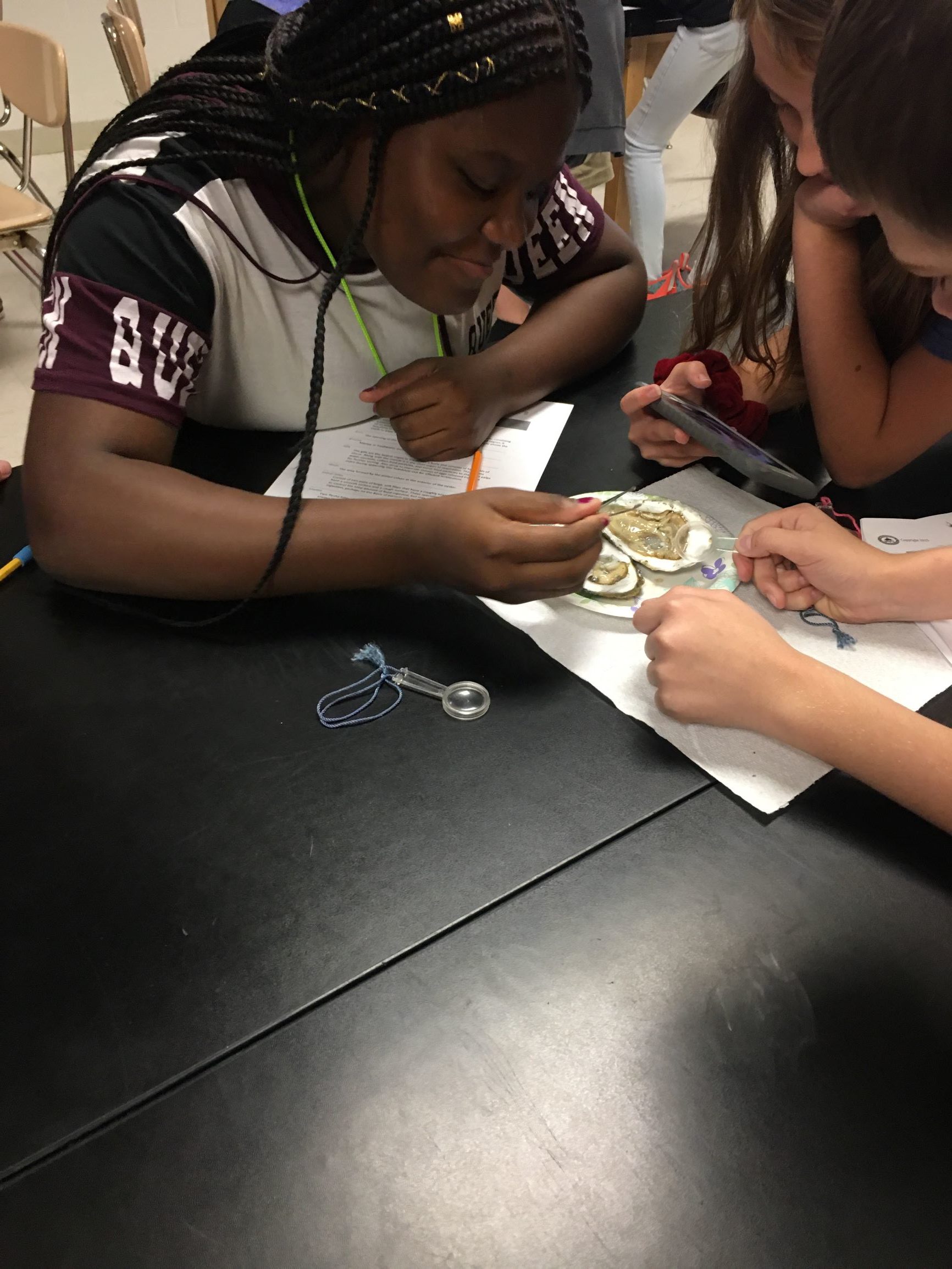

“I can see the gills! I wish I had gills!” one student at St. Clare Walker Middle School exclaimed while dissecting an oyster. Experiences such as these bring students one step closer to understanding and appreciating the importance of river stewardship.

Thanks to grants from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Association (NOAA), Friends of the Rappahannock provides a program called a Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience (MWEE) to students throughout the Rappahannock Watershed. MWEEs are designed to connect students to the issues affecting local waterways.

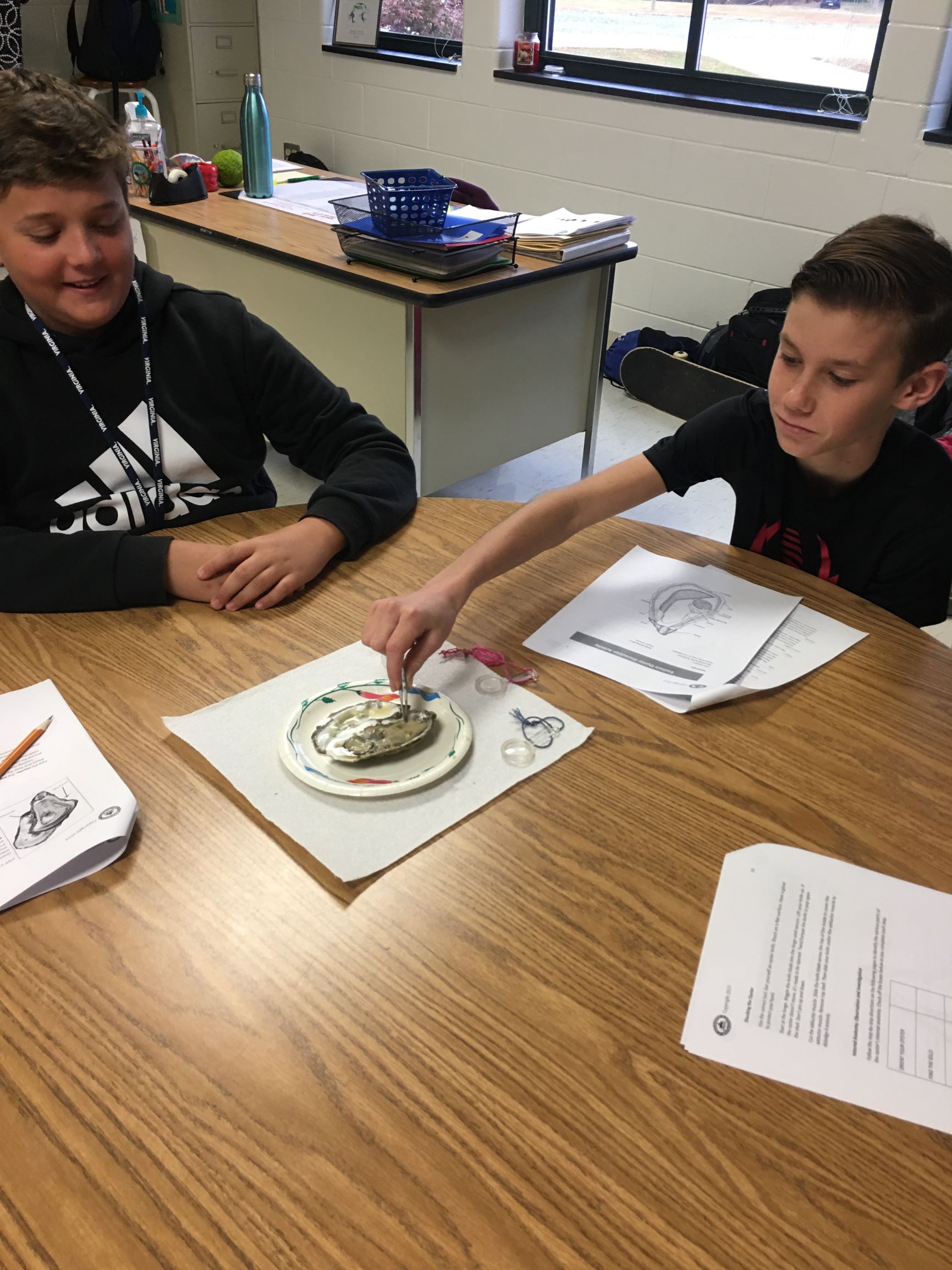

In Middlesex County our education team worked with 7th grade students from St. Clare Walker Middle School dissecting oysters. Dissection is part of the Virginia Standards of Learning so FOR was thrilled to connect an essential and relevant part of the local culture and economy.

During this visit educators began discussing the history of oysters and their connection to water quality in the Rappahannock.

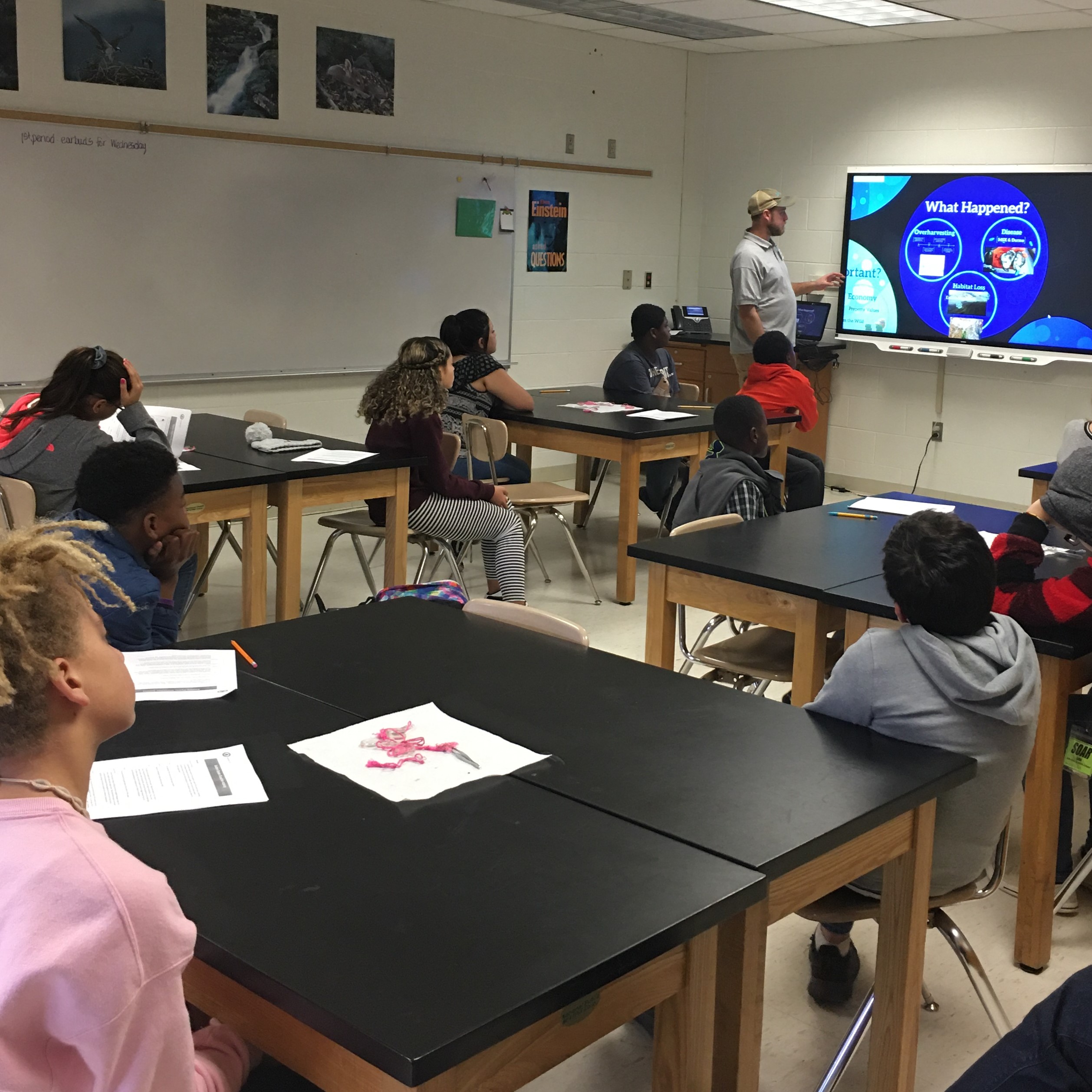

Students listen to Student Projects Coordinator Brent Hunsinger talk about the decline of the wild oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay. “In 1880, 20 million bushels of wild oysters were harvested in the Chesapeake Bay. Now we are lucky if we harvest around 400,000 bushels of wild oysters in the Bay.”

In less than 150 years, the native oyster has become one of the more valuable resources found in the Chesapeake Bay and Rappahannock River. So valuable in fact, oysters at one point were more valuable per pound than gold.

When students hear this and the difference in population numbers, they often ask, “So why did the oysters disappear so fast?” Here they have the opportunity to learn how disease, habitat loss, over harvesting, and sediment pollution affect how the oysters grow and develop.

After learning about oysters impact on the Chesapeake Bay and Rappahannock River, students then get to dissect an oyster for themselves. During the lesson students often have a variety of interesting comments coupled with turned up noses and wide eyes.

By the end of the dissections their differing demeanor turns into audible declarations of interest and excitement. Comments included, “That’s so cool!” and “Weird…”. After dissecting the oysters and learning about the filter-feeder’s history, students are ready to act.

Even students who may not like to eat oysters now clearly are connected to and are sensitive of an essential keystone species. Overall showing the students how the Rappahannock river is also their place instead of just a space brings hope for the future of our river.

They want to know what they can do to help save the oysters. Students discuss was to conserve water, reduce chemicals, volunteer for clean-ups, and be conscious of their impact.

Similar to how the small oysters impact the great body of water the Chesapeake, students can do minor things that will result in a greater impact for their watershed.

By Educator Lindsay Anderson and Student Projects Coordinator Brent Hunsinger